Have you ever wondered what it would be like to sit in on a Bethany class? Are you curious about the content and connecting together the name, photo, and classes taught by the professor? Or maybe you would simply like to pause the busyness in your life to learn more about mathematics, music, communication, chemistry, etc.?

Amid the Trees highlights the expertise of our professors at Bethany by inviting you into their classroom and seeing a sample writing of their outstanding work.

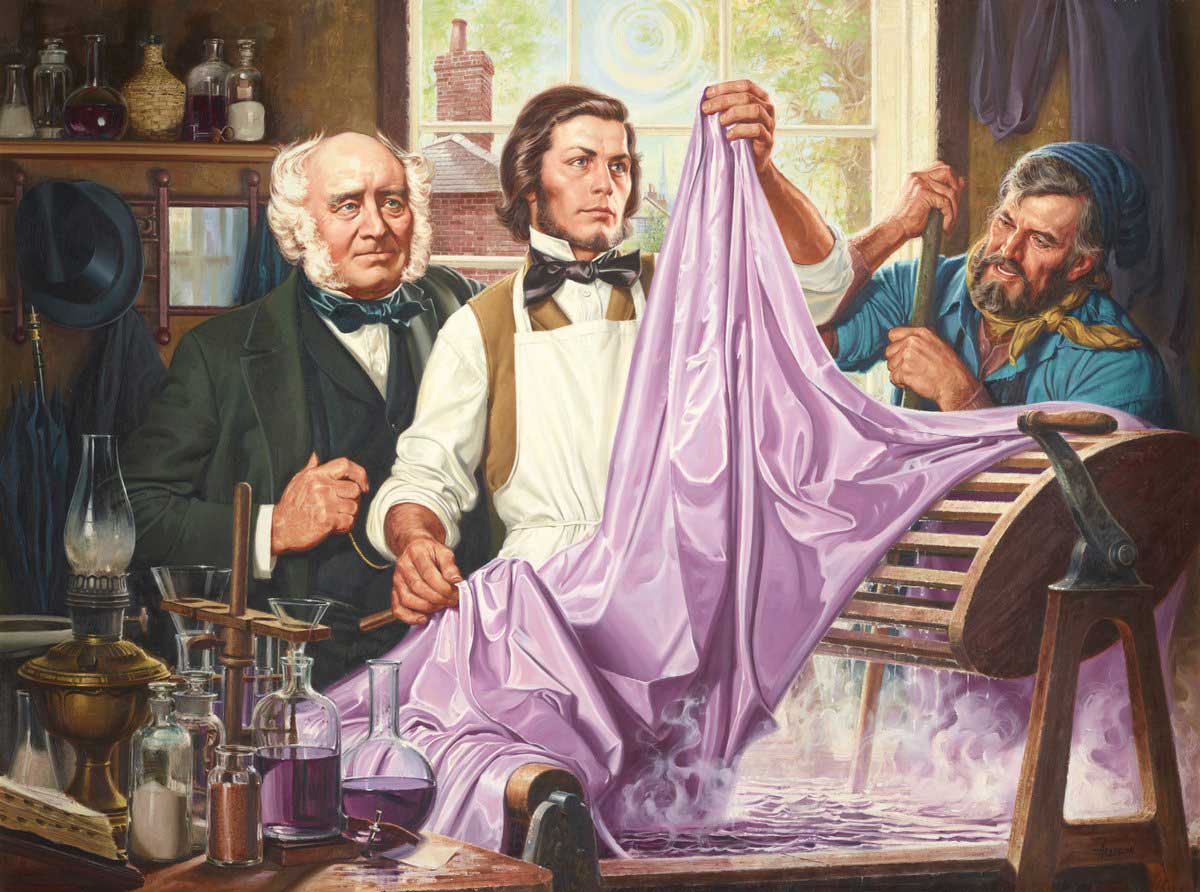

Chemistry and High Fashion

By Eric Woller, Professor of Chemistry

It’s late 1857 in London. You’ve settled down in the reading room of your Piccadilly mansion to enjoy a cup of tea and read the latest edition of the Illustrated London News. When you get to the fashion section, you cannot believe what you read. Described is an account of Empress Eugénie (wife of Napoleon III) arriving at a Parisian ball wearing a purple dress! Purple! Knowing her current preference for crinolines, the amount of purple dye needed to color this amount of fabric must have cost a small fortune, probably a large fortune!

You continue to read the account to find that this dress was not dyed with the exceedingly expensive Tyrian purple dye, which would have required the sacrifice of tens of thousands of Bolinus brandaris snails. No, this dye came from a chemistry lab right here in London created by an 18-year-old chemist.

It’s early 1856 in London. William Henry Perkin is working to synthesize quinine, a high-demand molecule to treat malaria. His experiments fail (the successful total synthesis of quinine would not be fully realized for another 144 years!), and he is left to clean up a mess of coal tar of undefined composition, a common occurrence in this line of work. He rinses the flask with ethanol to remove the oily crud. Some solution sloshes out of the flask, and Perkin cleans the spill with a white cloth. The white cloth turns purple! Purple!

This observation was not unique to Perkin. Many other chemists had observed similar colored compounds seemingly forming out of nothing from coal tar and its derivatives. However, exploring an observation like this to discover a practical application was rare. After all, organic chemistry during this time was primarily an academic exercise. Perkin had different ideas.

It’s late 1856 in London. 18-year-old Perkin has secretly worked on his purple dye, eventually called “mauve,” in a garden shed behind his house for several months. Perkin recognized that in his “failed” experiment, he oxidized aniline, which reacted with a toluidine impurity, creating the world’s first aniline dye. He had figured out how to make a synthetic purple dye. Now, he needed to scale up. He begged his father for a loan to build a factory. After much begging, his father loaned him the money, arguably to fund his son’s tenacious personality more than his son’s new, untested invention.

Eventually, thanks in part to the publicity provided by Empress Eugénie as well as Queen Victoria, Perkin made a fortune selling his mauve dye. More synthetic dyes followed from Perkin and other chemists. The clothing color palette quickly filled in over the next several decades. While the invention of the world’s first synthetic dye is historic, Perkin’s contribution to the development of industrial organic chemistry was of greater significance. Many dye-producing companies, like Bayer, soon focused their attention on pharmaceuticals, another organic chemistry industry.